Identifying Plants in Old and New Ways

Carl von Linnaeus, 1707-1778 (credit: public domain)

In 1735, The Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus developed a scientific method to identify plants. His "keys" systematically organized a plant's physical and morphological characteristics into a classification to use when trying to identify a plant species, genus, or family. By ranking features like petals, anthers, leaves, seeds, and bark, Linnaeus placed plants into these group identities based on the similarity of these characteristics. His Systema Naturae initiated the science of plant taxonomy, a basic hierarchy of what plant science would become generally. The Linnaean system unlocked the evolutionary wonders of the plant world. It is still used today.

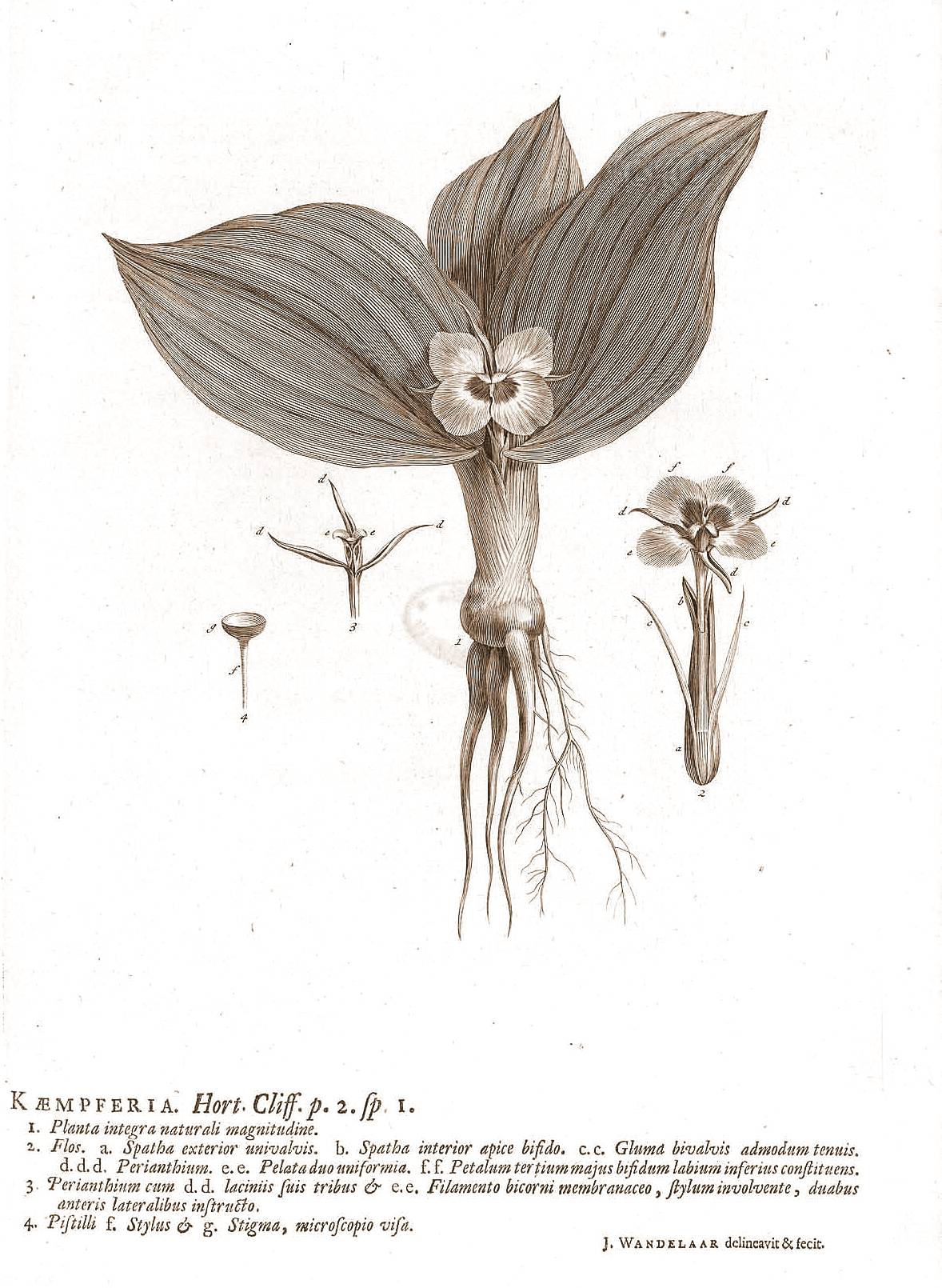

Hortus Cliffortianus, Linnaeus 1738 (public domain) Flower Arrangement Forms (credit: Claremont College)

Times have changed the 18th Century but the need to identify plants has not. New plant species continue being discovered and the need to determine their relationships on the 'tree of life' remains vital. DNA analysis, comparing samples of genetic sequences from different species, has confirmed many of Linnaeus's originally designations, but molecular studies have also re-ordered others into entirely new groups and relationships. The knowledge derived from DNA studies has greatly expanded the understanding of plant evolution. The first flowering plants appeared during the age of the dinosaurs, the Jurassic era 145 million years ago, and then exploded exponentially during the Cretaceous period that followed. Every landscape on Earth has plants adapted to it with even a few species grow in ice-free portions of the Antarctic Peninsula.

New technology keeps emerging that allows for more and more people to become involved in identifying plants even if they are not plant scientists. Tools for species identification can use a clever c-phone app that turns a smartphone into a taxonomic 'key' that can help to identify a plant while walking through a forest, in the mountains, or across a desert. The organization, Pl@ntNet, created Shazam to identify plants from their flowers, bark, and leaves by sending phone photos into their database. It then compares the viewer's images to what is digitally stored to help with an ID. As with digital maps that get can driving locations confused, digital plant ID's aren't perfect either. New A.I. models like Flora Incognita, that allow users to access more than 16,000 different plants simply from a photo, is expanding rapidly. With every new plant uploaded into the database, the proper ID is continuously improving. These democratizing tools can be used by trained scientists and interested plant enthusiasts alike. They offer 'citizen scientists' the ability to access Big Data sets and everyone benefits in the process.

Knowledge of plants will grow as more and more participants gather the relevant data. Increasing appreciation of plants has the added benefit of counteracting plant blindness, a serious contemporary malady. Previously, you needed to haul a bulky wooden plant press around to prepare collected field specimens. The dried and pressed plants were then sent to some dusty archive perhaps never to be seen again. Now, your cell phone can open a botanical 'world of wonder' allowing you discover plants in all their diversity and beauty. Plants can also become addictive. WHB