River Deltas Form Here and There

Okavango River delta (credit ISS, NASA)

The terminal outflow of a river creates a broad, geologic fan called a delta. The structures from when flowing rivers move sediments from uplands to lowlands, estuaries, or seas but there are exceptions.

Africa's Okavango River delta is one river that flows from mountains in Angola but hits a geologic barrier in the interior of Botswana. The river never reaches the sea. It is an ecological wonderland attracting photographers and wildlife enthusiasts from around the world during the rainy season as the region becomes a lush inland marsh.

According to NASA, the Okavango flows from the well-watered Angolan Highlands (upper image margin) and the flood waters slowly seep across a 100 mile-wide delta. The water finally reaches the fault-bounded lower margin of the delta in the middle of winter. This flooded wetland supports a vast diversity of plants and animals in the middle of an otherwise semiarid desert, the Kalahari. The entire Okavango system can be seen in a remarkable photograph captured by the International Space Station.

On Earth, another major river delta is produced by the Brahmaputra and Ganges Rivers when their flow ends among the mangrove swamps of the Sundarbans of Bangladesh. NASA's remote sensing Landsat satellite captured an image of the entire region containing waterways, mudflats, and forested islands. Wildlife in the delta includes tigers, sharks, crocodiles, freshwater dolphins, as well as vast array of bird species. The dark blue region represents a national park protected by both India and Bangladesh. The pressure of large human populations outside the park is seen in the lighter green, deforested areas to the north and west, outside the park's boundaries.

Brahmaputra River Delta and the Sundarbans (credit: NASA)

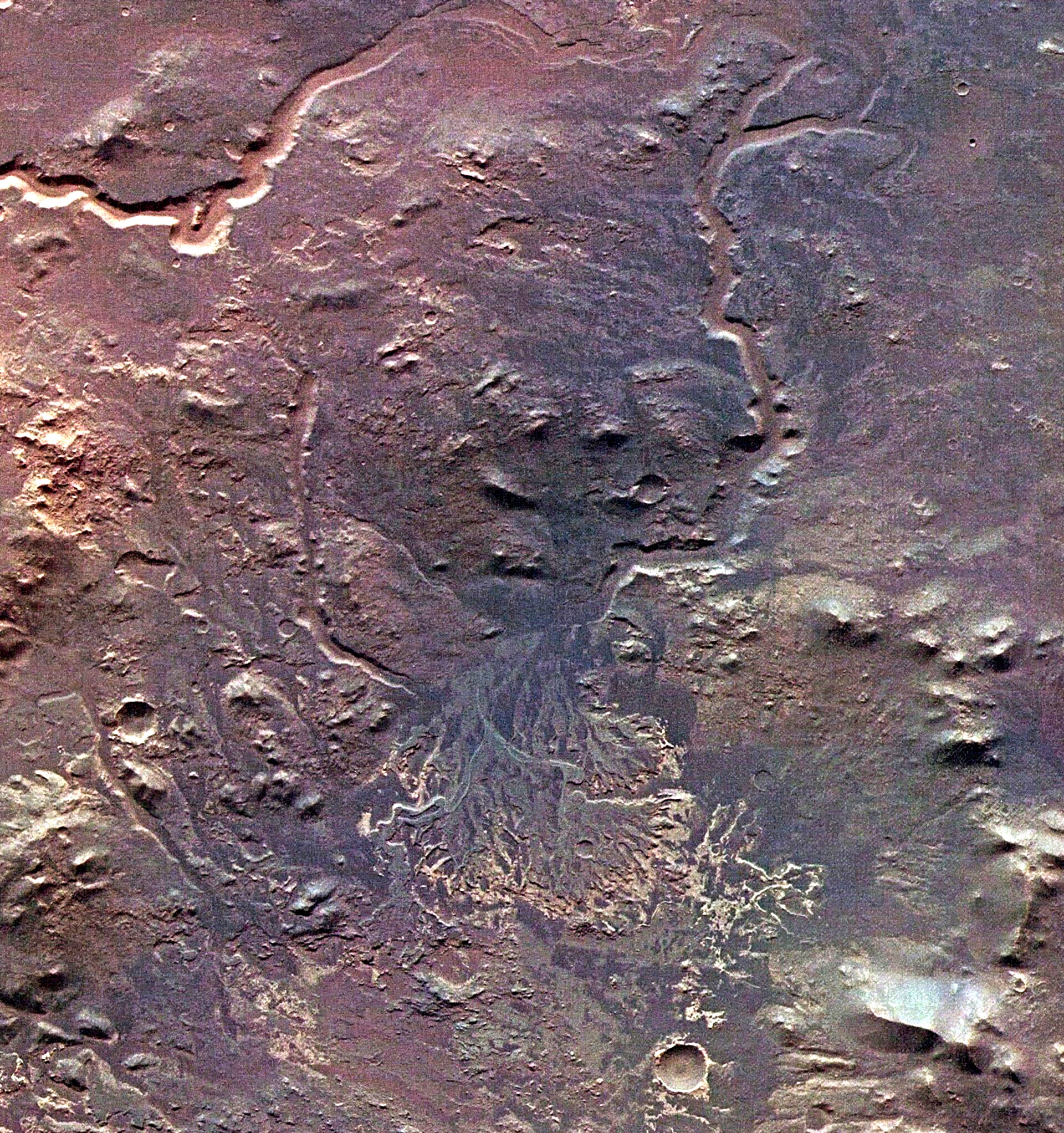

In earlier geologic eras, Mars also had flowing rivers of water that created deltas before the planet lost its atmosphere and surface waters evaporated or went underground. Fossil signatures remain that show meandering river channels which drained into a shallow lake leaving sediment tracks before the delta dried away. A fossilized delta is in the Eberswalde crater, in Mars southern highlands of Mars.

According the ESA, the delta with its "feeder" channels are all well preserved, covering an area of 45 square miles. Small, meandering channels near the top of the crater, would have filled the basin to creating a lake. After depositing sediments into the ancient lake, fresher sediments built up to cover both the channels and the river delta. These secondary sediments were later eroded by wind to expose an inverted, feathery relief of the delta's structure that exists today.

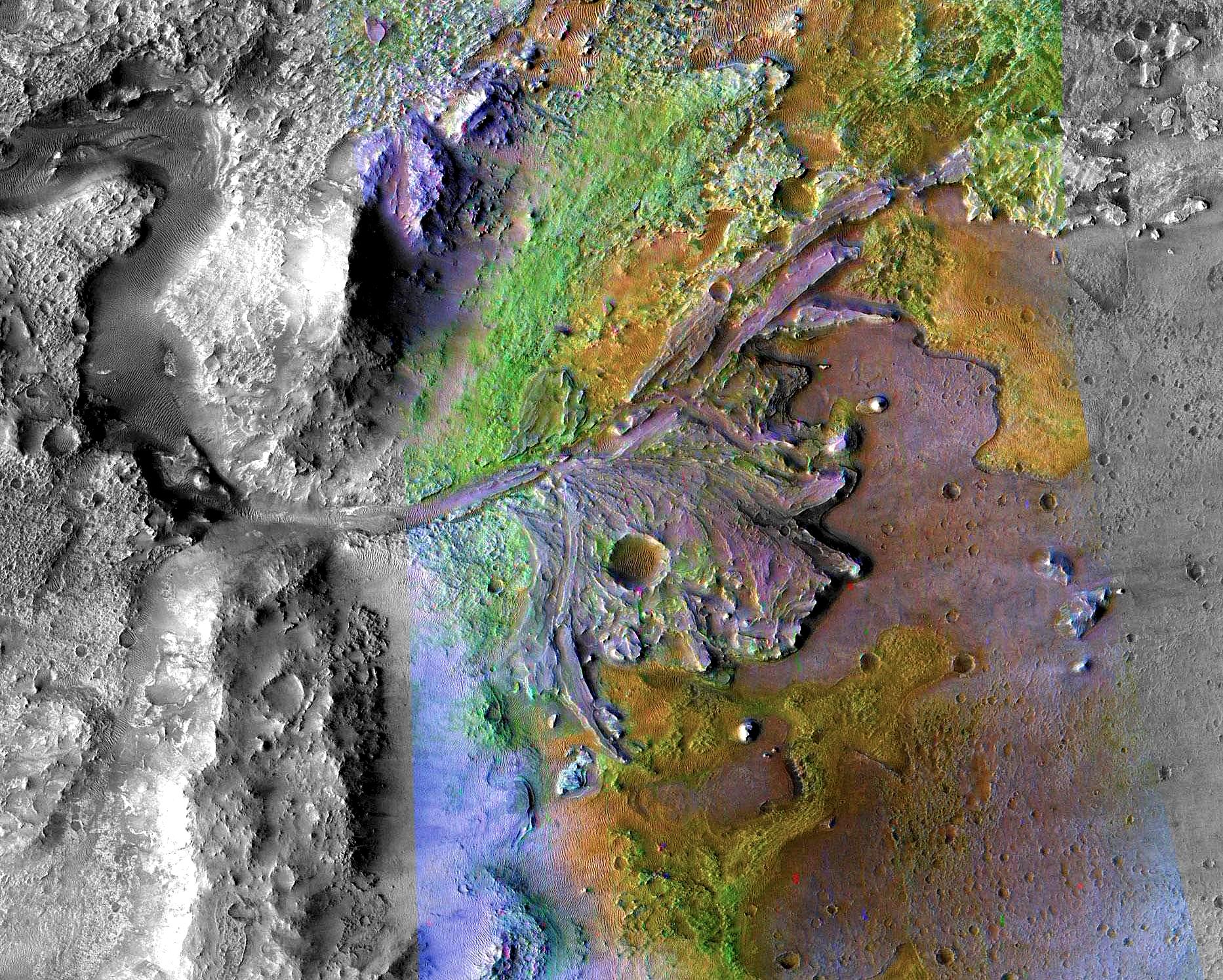

Another ancient Martian river delta exists within Jezero Crater and is one of the prime objectives for investigations by the Perseverance rover that successful landed near the frozen delta system. Perseverance is investigating if any spectrographic analysis might provide evidence of microscopic life had possibly existed there.

Ancient Mars river deltas: Eberswalde Crater (credit: ESA) & Jezero Crater (credit: NASA)

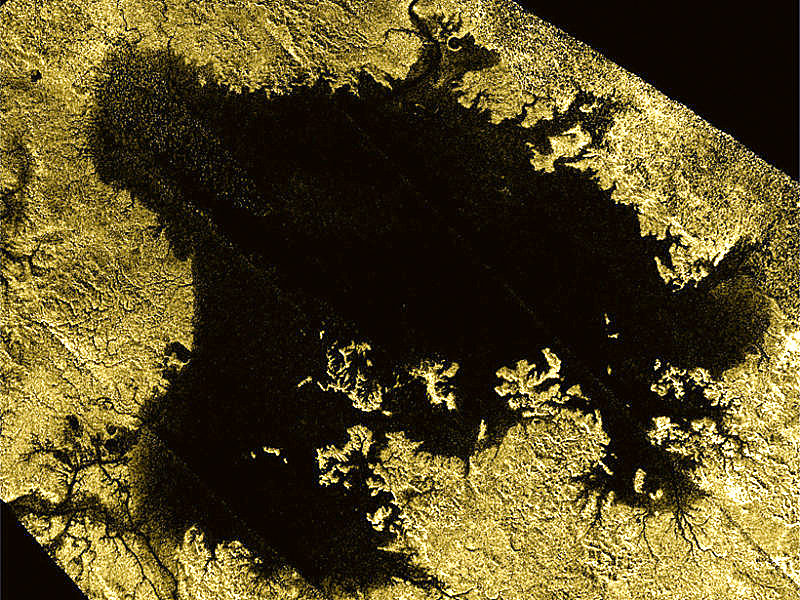

Stranger still are aquatic systems that exist and flow across the surface of Saturn's giant moon, Titan. The Cassini mission was in orbit around the ringed planet for 13 years prior to plunged into the planet once its nuclear fuel became exhausted. During Cassini's tour of Saturn, the robotic laboratory surveyed many of the gas planet's moons and used it radar system to peer through Titan's thick, smoggy atmosphere.

During these orbits, the probe captured images of rivers and lakes on Titan, consisting of liquid ethane and methane at -290F, but deltas appear to be missing. The mystery of why liquids on Earth and Mars carried sediments which formed deltas when deposited and not similarly on Titan, may be due to temperature differentials between the moon's liquid hydrocarbon rivers and the seas they empty into. It is also possible that some geological or chemical issue is at work there that is unique to Titan. Future missions to investigate this strange moon may solve that mystery. WHB

Titan Lakes (credit: JPL/Caltech/NASA/Cornell))